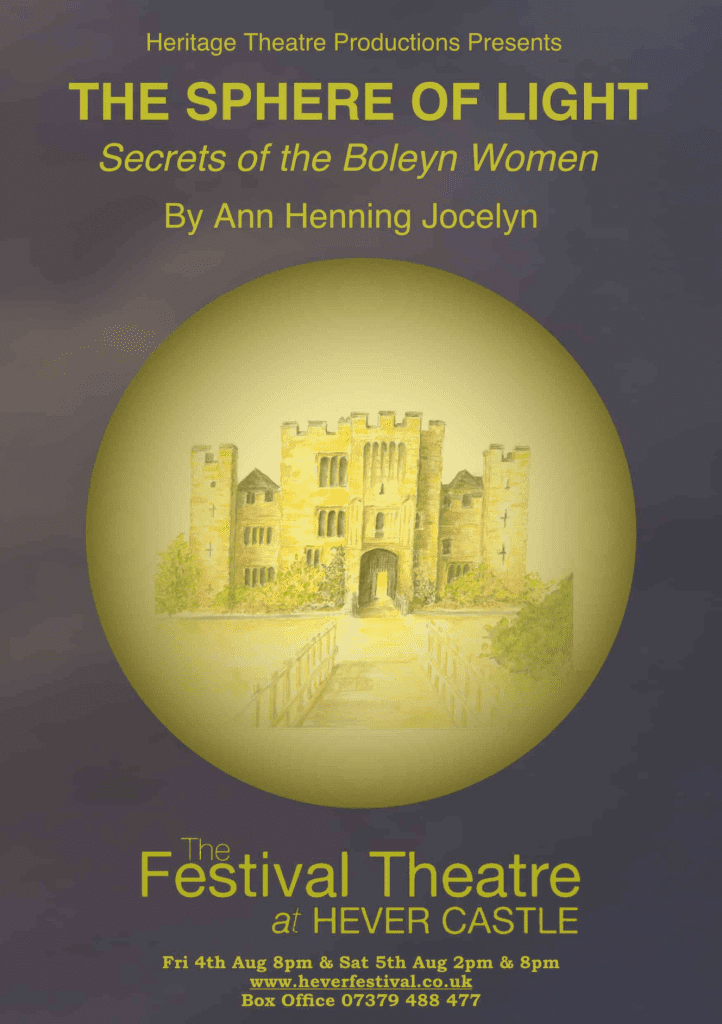

“After Hilary Mantel and Alison Weir, is there room for more on the Boleyn story? Actually, there is. It is an engrossing story, and Jocelyn deserves credit for finding a lucid structure in which to unravel it once more, getting the balance right between the complexities of family and court politics under Henry VIII.”

Dr Tim Hochstrasser

The Sphere of Light unfolds like a detective story, exploring the many mysteries surrounding the fate of the Boleyn family. Whilst thoroughly researched and well endorsed by Tudor scholars, the play is a character-driven drama focused on gender dynamics and as such timeless and universal.

The author’s interest in the subject stems from her marriage to a descendant of Lord Hunsdon, son of Mary Boleyn and, presumably, King Henry VIII. Decades of research opened up many unanswered questions, until finally an ancient tombstone found at an Irish Tudor castle provided the cue to a highly plausible scenario.

“Ann Henning Jocelyn is to be commended for taking a complex and layered moment in history and presenting it in an accessible and engrossing way. To attempt to change the narrative of such an already documented era is a bold choice –and one that works very well.”

The Tandridge Independent

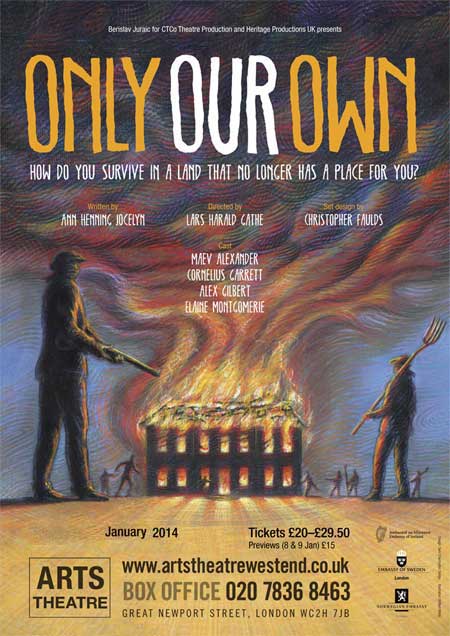

Hailed by London critics, Only Our Own follows three generations of an Anglo-Irish family finding a place for themselves in modern Ireland. The play pays tribute to the assimilation achieved today but is also a reminder that this did not happen lightly or overnight.

Looking back to the 1920s, when hundreds of stately homes were burnt to the ground and the owners’ ancestral lands seized, the play explores the struggle of one family to survive – emotionally, culturally and socially – in a rapidly evolving political landscape.

Implicit in between the lines is also the story of Ireland. Reflecting an imposed social system that created many innocents victims, Only Our Own follows one nation’s journey from a highly polarized society to a modern integrated one, ready at last to rise above age-old bitter divisions.

On a personal level, the play explores the dilemma of living with or without a traumatic past; the inter-generational gap between people emotionally linked but faced with different life options; and, ultimately, the need to develop and adjust as the world changes around you.

“Family Drama in Trinity”, Irish Times, April 18th, 2015.

“Exploring the Protestant Experience at the Samuel Beckett Theatre”, Irish Examiner, April 22nd, 2015.

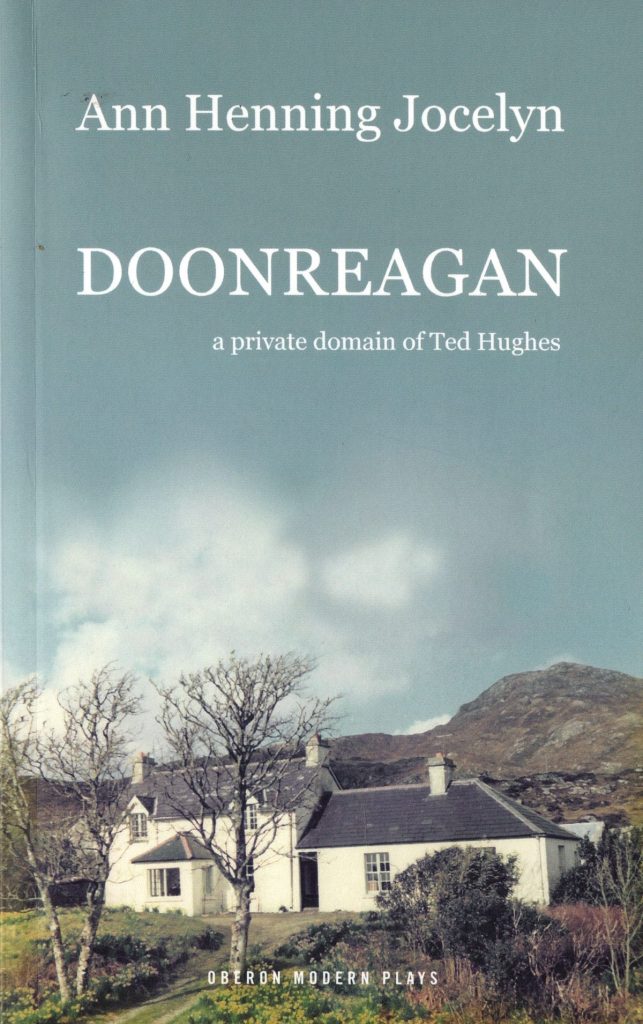

Doonreagan House stands on the curve of Cashel Bay in Connemara, on Ireland’s remote west coast. Behind it, under a wide summer sky, looms a high outcrop of rock and peat, wild as the miles of mountain and moorland that separate the village of Cashel from the nearest town. It was here, in February 1966, that Ted Hughes arrived with his married lover, Assia Wevill, and three children: Frieda and Nicholas, Hughes’s children with Sylvia Plath, who had taken her own life in 1963; and Shura, his daughter with Wevill. It was a self-imposed exile – a chance for Hughes to write, and for he and Wevill to seek a level of domestic normality that had eluded them since they’d begun their affair four years before. They would stay at Doonreagan for just a few months, but these would be some of their happiest together: Hughes began working on his acclaimed verse cycle Crow, while Wevill wrote and painted, and Frieda attended the village school. Decades later, Hughes would claim that his time in Ireland was one of the most productive periods of his writing life: not least because here, miles from London, he felt far from the corrosive gossip that had dogged him since Plath’s death. Here, too, he and Wevill could live in privacy. Almost none of their friends and family knew she was here.

“The little known Connemara interlude in Ted Hughes’s life.” Irish Times, January 19th, 2015.

“I saved myself from being bullied with the plays I wrote.” Galway Advertiser, January 15th, 2015.