August Strindberg.

Sometimes I’m asked how I became a playwright. It’s a difficult question to answer. I’m not sure anyone ever becomes a playwright. It’s more a case of recognizing the fact that you are one.

The Swedish playwright August Strindberg took the view that every play is born out of a secret. That plays are written when something is clamouring to be said that can’t be expressed in any other way. It helps, of course, if you have some working knowledge of theatre as a medium. The Norwegian playwright Jon Fosse maintains that plays write themselves: they take shape in your mind, and all the author has to do is listen carefully and record what’s being said. Eugene O’Neill, likewise, would never put a word down on paper until a play was fully formed in his head.

This may be the reason why a good drama can take years to develop. Why plays commissioned to a deadline are rarely as good as those that have been given the time they require to mature. Why most great playwrights throughout history have left behind no more than a handful of truly excellent plays.

I was nine when I first attempted playwriting. As part of a History project at my school in Sweden, I volunteered to put together a tableau about the 15th century folk hero Engelbrekt, confronting King Erik over crippling taxes imposed by the Crown. The school performance saw me handsomely rewarded to the tune of 25 öre – the equivalent of 2 pence.

After that I went on writing plays. They were conceived and rehearsed in the basement of my best friend’s house, which her nondescript, conventional parents had transformed into an amazingly inspirational, evocative space – like something out of a fairy-tale. I still have some of these scripts, and looking at them now, I’m surprised to see that they were in fact properly structured, with acts and scenes, and well defined plots and characters.

I have no idea who taught me the rudiments of dramatic art. I remember being taken to see classical plays for children at the Gothenburg City Theatre. I loved seeing the sets and costumes and the stories unfolding, but often found the acting too obtrusive. I had come to enter an enchanted world, lose myself in its magic – not to have the spell broken by a contrived performance.

My early writing was driven by a similar wish to escape reality, away from much sadness and tragedy in my family. Though the plays were regularly performed at school, I wrote them merely to please myself. But one event in the late 1950s stands out as a milestone.

The world had been hit by a serious pandemic called the Asian flu. It struck you down for weeks, and I had suffered like everybody else. Finally I was able to return to school. As I was walking along that morning, I found to my horror my path blocked by the person I feared most: the class bully, who had long had me as his favourite target, subjecting me to regular beatings, which, like most victims, I was too scared, and too ashamed, to report. Now, in my much weakened state, he was the last person I wanted to meet, and I could feel my knees trembling as he approached me. “So you’re well again?” he growled, to which I couldn’t but timidly agree. “And have you written a new play?” he demanded. I said I had – it was the only thing I’d been able to occupy myself with during my convalescence. “Thank God for that!” he exclaimed, slapping my back. “We haven’t had a good laugh since you’ve been ill!”

This was the moment when I realized that my writing was not just for myself but also for others. It meant I had something of value to offer, appreciated even by my worst enemy. I also knew that, as long as I kept providing the entertainment, I would not be bullied again.

So I kept producing plays. But I ran into a problem with censorship. I had been asked to write a play to mark the beginning of the Easter holidays and had conceived what I thought was a perfect plot. The main character, Mother Hen, is given the great honour of laying two eggs for the king’s Easter breakfast. But at the start of the second act, she comes rushing in, literally in a flap, crying out: “Oh dear, oh dear, what will I do? The king’s eggs have hatched into two chickens! I should never have got together with the cock the other day!”

On the morning of the performance, my mother caught sight of the script and perused it. “What kind of filth is this?” she called out. “You can’t have this in a school play!” I couldn’t understand her concern. We had been taught at school that hens lay eggs for eating, but if there is a cock present, the eggs hatch into chickens – what was wrong with that? “It’s inappropriate,” was the only explanation I got. “This line has to be cut!” I protested in all innocence that this was what the play was about. If I cut that line, the whole plot would collapse. But she wouldn’t budge. The line had to go. And though everyone still seemed to enjoy the play, as far as I was concerned, it was a dismal failure.

I’m relating all of this because it is symptomatic of my career as a playwright: a repeated pattern of writing what I have to write, seeing it applauded where I least expect it, and occasionally having the heavy hand of authority coming down to stifle what I myself consider to be utterly sound and reasonable.

Epidaurus.

At second level, I didn’t write at all. Like most teenagers, I was anxious to conform, afraid of doing anything unusual that would single me out. Aged fifteen, I was told by a vocation guidance councillor that I was a perfect cut for an industrial chemist and accordingly made to choose natural science subjects for my final three years. But after two years of studying maths, physics, chemistry and biology, I rebelled. Not because I had anything against natural science – but because I had so little in common with my class-mates. I thought, how can I spend the rest of my life surrounded by people who are so unlike me? My best friends were all doing Classics. My mother, herself a Classics scholar, supported my decision to switch courses, even though it would mean working through the summer holidays plus repeat a year.

All the teachers did their best to dissuade me. What kind of career could I hope for knowing Latin and Greek? In fact, only a year after I left school, these studies were abolished in Sweden as having nothing of value to offer modern society.

And yet… I think it’s the best thing I ever did. The study of Latin and Greek gave me a fundamental understanding of language and how it works. It has helped my command of numerous foreign languages and made it possible to use an acquired language as my own. Not least – it gave me a chance to read the ancient dramas in their original version. As part of the course we performed our own Swedish translation of Antigone, and the power of its speeches made an impression that has never left me.

The Classics studies also introduced me to another favourite subject: History of Art, and when it came to choosing modules for my university degree, I settled for History of Art and History of Literature with the Accent on Drama. It’s interesting to note the composition of the drama course. At a rough estimate, the study of Scandinavian and French plays took up about fifty percent. The rest was taken up to a more or less equal amount of German, Russian, Spanish, Italian, English, American and Irish plays. It allowed for one play by Shakespeare, but included the whole range of French classicists. France of course had been the main influence on Swedish culture for centuries – we had a French royal family and in days gone by, French was the language spoken by the upper classes. Strindberg, our great dramatist, spent much time in Paris and even wrote some of his work in French. He was – and remains – a favourite of mine, and I wrote my undergraduate thesis on his chamber plays.

However, we were now at the end of the Swinging Sixties, and we were all aware that the centre of contemporary culture was London, especially for young people. So, armed with my degree, this is where I went, to check out the English theatre scene. Two of my friends, who were Swedish actors, were doing a course at the London Drama Centre, and through them I was directed to an audition for a Leroy Jones play directed by the American Ed Berman. It wasn’t much of a role – a lightly clad vestal virgin – but I got the part and so found myself on stage at the ICA just off Trafalgar Square within weeks of my arrival.

Charles Marowitz.

My other London contact was the American director Charles Marowitz, who had his own theatre called The Open Space in Tottenham Court Road. A brief interview with him led to an offer of work as an intern.

Marowitz is now referred to as one of the world’s ten most important theatre directors of the twentieth century. He first made a name for himself working with Peter Brook at the Royal Shakespeare Company, launching the Theatre of Cruelty season, advocating an artifice-shredding theatre that stimulated the audience’s fundamental fears. One major production was Marat/Sade by the Swedish playwright Peter Weiss. His theatre went further than presenting actors in performance on stage: it offered a first-hand experience of the human condition, with the capacity of reaching the deeper layers of our consciousness, not only stimulating and inspiring further thought, but also enriching and intensifying emotions.

Before going on to run his own theatre, Marowitz had also been working in the West End with names like Joe Orton, Sam Shepard and Eugene Ionesco. But it was his irreverent, provocative adaptations of Shakespeare that gave him international recognition. His absurdist collage of Hamlet has been described as “theatrical dynamite”. I shall never forget his version of The Taming of The Shrew, where he turned Shakespeare’s light-hearted comedy into a feminist tragedy, with Kate’s final speech transformed from a show of facetious coquetry into an enforced confession whipped out of a subjugated, terror-stricken victim.

Marowitz had had good experience as a guest director in my home town of Gothenburg, and I think he had an affinity with the modern Scandinavian theatre tradition that had grown out of Ibsen’s social engagement and Strindberg’s expressionist drama. Charles’ approach to theatre made eminent sense to me – I was able to emulate it without question, and my work as his assistant progressed smoothly. This in itself was remarkable, as Marowitz was notorious for alienating people with his abrasive manner and quarrelsome nature. He took a gleeful contrary stance to anything he considered phoney or commonplace. His profound disdain of British mainstream theatre was expressed in incisive, witty and acerbic criticism, often to the point.

I myself had nothing but sympathy, encouragement and support from him. I regret now that I took much of it for granted. I was too young and inexperienced to realize just how favoured I was having such a brilliant mentor.

Notwithstanding names like Andy Warhol and Pablo Picasso on the repertoire, and talented young actors such as Glenda Jackson and Philip Schofield, The Open Space Theatre operated on a shoe-string, and I received no pay for my work. Some of it was very exciting, like discovering the script for the Chicago Conspiracy Trials, which Marowitz later produced. But impatient for a more intense learning curve, I decided to audition for a London drama school. Charles’ business partner, Thelma Holt, recommended a place called Studio 68, set up by actors Sean Connery and Robert Henderson, with a view to letting drama students do professional productions as part of their training. I auditioned with two pieces rehearsed by Marowitz – one of them Miss Julie – and was accepted.

Studio 68 prided itself on being progressive. While our instructors were recruited from venerable institutions such as RADA and LAMDA, they were given more freedom here to do experimental work. One of our tutors is now Head of Drama at Berkeley University, one acts as movement advisor to major period TV drama, and another has been given an MBE for his management of the Orange Tree Theatre in Richmond. An invaluable part of our physical training was in the Alexander Technique, which has stood me in good stead all my life. For those of you unfamiliar with this method, it’s much used by actors and musicians as a means to relieve physical tension.

The work we did at Studio 68 was varied and ambitious. It taught us a lot, not only about stagecraft but also about ourselves and each other. Much of it was more like shrink sessions, and I’m not sure it made us excel as actors. In fact, only two members of my group went on to have a successful acting career. Among the others, one is now a New York stage director, another an American film producer; one is Head of English at Toronto University, one a best-selling author and one internationally renowned as an expert in stage movement.

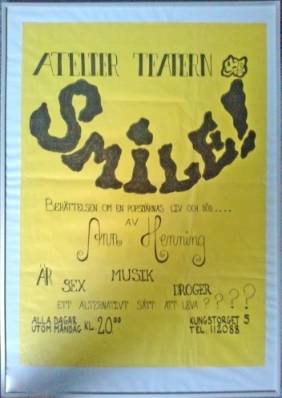

“Smile”.

While still at drama school, I returned to writing for the stage. I had had some personal experience of the London world of rock’n’roll, and been quite distressed by what I witnessed. This was the period that saw the deaths of Brian Jones, Jim Morrison and Jimi Hendrix – all at the age of twenty-seven. My play Smile was about a rock star hounded to death by ruthless commercial interests, taking with him his girl-friend, my own alter ego.

I showed the play to Charles Marowitz, who was very encouraging but explained it was “not his scene”. So instead I sent the script to the Atelier Theatre, a leading fringe theatre in Gothenburg.

Towards the end of my two year drama course, I was offered a part in a play with Charles Marowitz: “Sam Sam” by Trevor Griffiths. It led on to steady employment at the Open Space: as an actress, assistant director or ASM, whatever was required, all to the princely wage of six pounds a week.

It wasn’t easy to survive on that income, and when I eventually heard from the Atelier Theatre that they were keen to do Smile, I decided to return to Sweden. Once there, I was also offered a job as a member of their permanent acting troupe. I appeared in two productions – one about political prisoners, the other about homelessness – and then it was time for my own play to be produced. Apart from providing the Swedish translation, I elected to stay out of it,. The director chosen for Smile was one with personal experience of the rock scene, but unfortunately, this landed him in rehab two weeks before the opening. Finding a suitable replacement proved impossible, and the only way to save the show was for me to take over. I had learnt enough from working with Marowitz to do my own directing, and when the play opened, it was well received by critics. However, I encountered some unexpected opposition.

The Gothenburg City Theatre, a dominant cultural institution, had turned itself into an active political organ. The members of the permanent company had joined the Communist Party, seeing as their mission to transform the role of theatre in society. Concepts such as playwrights, actors and directors, as well as stage hands and cleaners, were done away with. Instead, all employees were referred to as “theatre workers”, acting together as a group on an equal basis, devising productions collectively with the sole aim of raising social awareness. In defiance of all commercial interests, theatre was expected to be funded by state and local government.

There was a famous incident, where a well-known actor took to the stage to address a traditional first-night audience, dressed up in their usual black tie finery. He told them that Bourgeois scum such as themselves were no longer welcome in the theatre, and from now on, they’d be well advised to stay away.

Word was passed on to me through a powerful agent that Smile had been denounced as politically unacceptable. I protested that it was in full agreement with the ethos of the City Theatre, exposing as it did the merciless exploitation of talented young musicians. I, too, believed in theatre as an instrument of social change. I, too, was against crass commercialism, and I, too, denounced petty Bourgeois values – I hadn’t become Marowitz’ acolyte for nothing.

To no avail. Smile was said to glorify celebrity, and plays should be about down-trodden working-class people, depicting their miserable conditions with a view to empowering them politically. If I was to continue working in Swedish theatre, I would have to join the Communist party and change my tune. I would also have to give up things like make-up and smart clothes, food delicacies and domestic comforts. And I would definitely have to get rid of my dog. How could anyone spend money on dog food when there were people starving in the Third World? All of these were symptoms of despicable middle-class habits, in breach of the Communist manifesto and enough to stamp me as a Class Enemy.

One political journalist had the audacity to suggest that such extreme radicalism carried within it the seed of its own destruction. But rather than hang around waiting for that to happen, I packed my bags, found a good home for the dog and took the boat back to England.

London World Trade Centre

In London, my personal and artistic freedom had never been called into question, but now I was presented with more pressing challenges, such as how to survive and how to avoid being deported. No longer a student or employee, and with Sweden not yet a member of the EU, I was persona non grata as far as the authorities were concerned. At The Open Space someone else had taken my place. Equity would only let me play foreign parts, and sporadic work in films and commercials, usually as an au pair or a prostitute, did not bring in enough money to live on. An agent had taken on Smile but had no success placing it.

My friend George Hulme, himself a successful playwright, had one piece of advice to offer: “To succeed as a writer,” he said, “the one thing you have to do is buy London property.” His theory was that it would give me the option of letting out my London home and going to live more cheaply elsewhere. The steady income would give me the freedom to write: what, how and when I liked, without ever having to compromise my talent in order to pay the rent. At a time when I had hardly enough money to eat, I dismissed his idea as ludicrous.

An episode with a turnip, of all things, brought things to a head. I was down to my very last shilling, equivalent to about five cent, and took a trip to the North End market too find something to last me for a few days while I waited to hear from my agent and attended more auditions. My shilling yielded a pound of turnips – three of them. One for each day, I reckoned, would sustain me, until something turned up. But as I put on the first one to cook, my electricity ran out. The meter needed shillings to feed it. I was left with three raw turnips.

That’s when I walked all the way from Chelsea to the City of London in search of a regular job. I managed to land one – as a linguist at the London World Trade Centre, to a generous income of twenty-five pounds a week. But apart from acquainting me with my future Irish husband, that work was merely a stopgap: a means to an end. Still – it was here that it dawned upon me that I possessed one skill that few Londoners could compete with: my command of Swedish. Armed with that, and a degree in English added to my other credentials, I embarked on a new career as a free-lance literary translator.

Before long, I had all the commissions I could wish for. The work with leading English and Swedish authors – the only ones considered worthy of translating – helped me perfect my English and taught me a lot about good writing. They included Ruth Rendell, Joanna Trollope and Nobel Laureate Kazuo Ishiguro. In due course I was elected Chair of the English Translators’ Association, and for six years represented literary translators on the committee of the Society of Authors and at international congresses across Europe and in the then Soviet Union.

In the UK I remained an undesirable alien, until I managed to get a permanent British visa through working on and off as an interpreter for the British Foreign Office. This was very interesting, as many talks I attended were at cabinet level. Another delightful engagement was as a scout for a Swedish theatre producer. This meant being paid to go to the theatre but got me into a bad habit of walking out in the interval if the performance wasn’t good enough to merit a positive report.

Ingrid Bergman.

At one time, I spent nine months in close collaboration with the London-based film star Ingrid Bergman, who was writing her memoirs and needed someone to handle the Swedish research material and produce a Swedish version of her book. The time I spent with this charismatic lady left a memory I shall always treasure. What impressed me most was her whole-hearted commitment to the task in hand – perhaps this was the key to her great success as an actress. While our work was on-going, every other part of her life was pushed aside; the English ghost writer, Alan Burgess, and I felt as if we were the only people who mattered to her. It followed of course that, as soon as the book was delivered, we lost her to her next project, starring in a film as the Israeli politician Golda Meir.

Although my ambition was always to write my own stuff, I got so much enjoyment out of translating novels, films and plays, it was a surprise to find that it also paid well. What had taken me a week to earn at the Open Space I could make in an hour of translating. And within a few years I had saved up enough money to do as George Hulme had suggested: buy myself a flat.

In 1982, thanks to my regular contacts with Swedish and English publishers, I was commissioned to write a book of my own. It was with a view to putting the finishing touches to the script that I first went to Connemara, where my Irish friend from the World Trade Centre had offered me the use of his holiday house. I had intended to spend six weeks there, but as it happened, I never went back. I’m still in the same house. I’m married to the owner. And I still let my London flat.

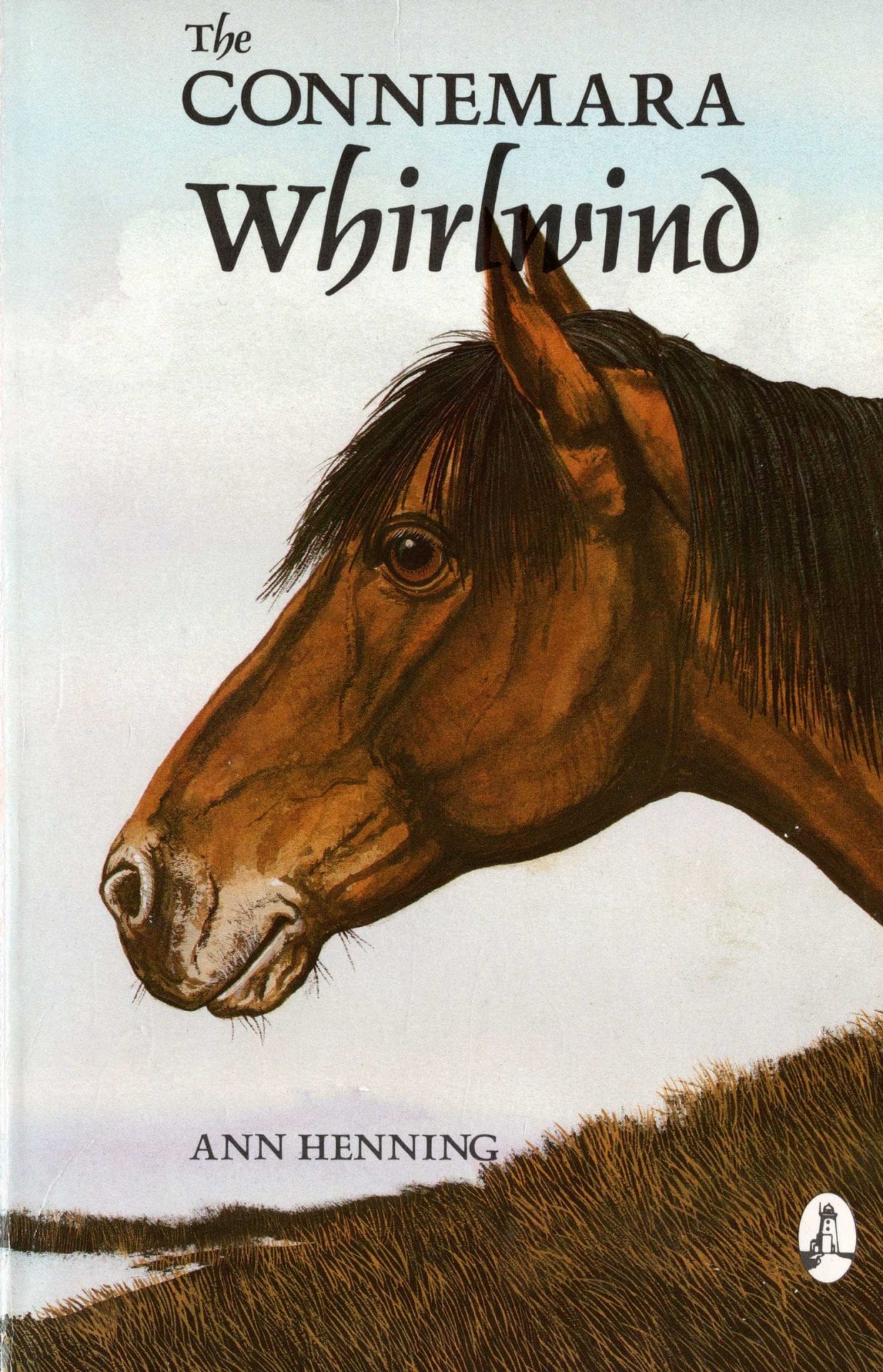

“The Connemara Whirlwind”.

Having been through it twice, I can testify that it is not easy for a writer to switch from one culture to another. Once my book was published, I decided to give myself a break in favour of another great interest: horses. Finding myself in the heart of Connemara pony country, I soon became involved in the breeding and training of these lovely animals. The work brought a welcome commission from an Irish publisher. My trilogy about the Connemara Whirlwind, inspired by my own stallion, became an instant bestseller; it is still, after twenty-five years, available in bookshops, read in schools and popular as an exam project.

Both publisher and readers expected me to go on pursuing this successful formula, but after the third book in the series I decided to call it a day. I was missing the theatre. Ever since my arrival in this country I had been an active member of the newly formed Society of Irish Playwrights, and through this connection I came to chair the judging panel of the O.Z. Whitehead playwriting competition. It also led to my appointment in 1996 as Artistic Director of the fourth International Women Playwrights’ Conference, to be held the following year at University College Galway.

This conference attracted nearly three hundred female delegates from all corners of the world. Having ploughed through hundreds of submissions, I selected about seventy plays for presenting over the five days, from rehearsed readings to full productions. I grouped them into themes, one for each day, to give a fascinating insight into the way different cultures handle similar topics. I had some trouble with militant feminists who attempted to hi-jack the conference, objecting to men being admitted to see the performances; but over the years, the artistic benefits of this event have been confirmed time and again.

1997 was also the year when fellow-playwright, Máire Holmes, and I formed the Connemara Theatre Company, with a view to introducing professional theatre in Connemara. The project met with a singular lack of enthusiasm, first from the Arts Council, then from local people who, used only to amateur theatre, could not see the point of going to see a play with none of their friends appearing in it. The business community wanted to take charge of the venture, including artistic control, but were not prepared to help fund it. In the end we went ahead without official support, but faced an uphill struggle, made infinitely worse by the sudden death of Máire’s husband, Tom Breathnach, who was our administrator. Nevertheless, we persevered for five years, presenting as many professional productions in venues all over the country. But the efforts to make ends meet were so draining they excluded all creative work, and in the end we gave up.

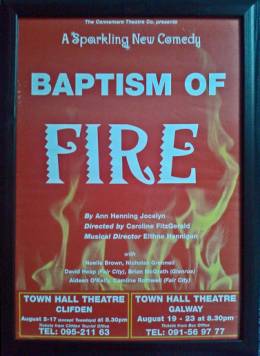

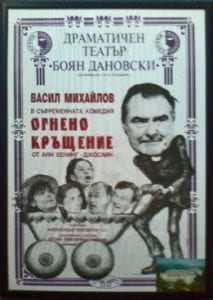

“Baptism of Fire”.

The Connemara Theatre Company provided me with an opportunity to take up directing again, and also produced two of my own plays, the first a comedy of manners called Baptism of Fire, featuring a cast of well-known Irish actors. This was a play that gave audiences something they could relate to: a humorous affirmation of shared values. I had always liked the idea of making people laugh. One of my London friends, Terence Frisby, had had a tremendous hit running for years in the West End and on Broadway: the comedy There’s a Girl in My Soup, later filmed with Peter Sellers and Goldie Hawn, and from him I had learnt a fair amount about the technique of writing comedy.

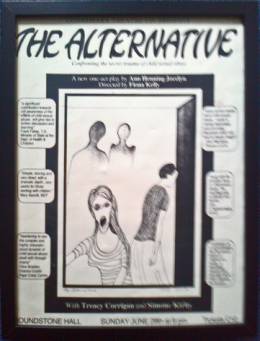

“The Alternative”.

The other play, called The Alternative, was more serious: true to my Scandinavian conditioning, I had chosen to write about a social issue that I felt badly needed attention: child sexual abuse in the home. Focusing for the first time on answers to the burning question “Why?”, I wanted to start a debate that would provide a helpline, providing answers to those who needed them most. Discussions about the situation depicted in the play would raise much awareness, whilst keeping everyone at a safe distance from personal implications. The play was endorsed and recommended as mandatory viewing by all Irish childcare agencies. Audiences thought otherwise – as one person put it: “Who would want to see play like that?” Posters for the play were torn down overnight, and schools ran for cover at the prospect of having it performed. Also, I discovered that the theatre community was prone to dismiss so called “issue plays”, on an assumption of scant artistic merit.

“Baptism of Fire”.

Baptism of Fire, on the other hand, had a successful run at the Galway Town Hall Theatre, and in March 1999, I was invited to attend its Bulgarian premiere. My arrival at Pernik, close to the Jugoslav border, brought more drama than I had bargained for, as it coincided with the start of NATO’s bombing of Kosovo. Bomber jets could be heard flying over the theatre, and all the Bulgarians was very nervous about an escalation of the conflict to include their own country. At the dress rehearsal, I was taken aback to see that my play, with its elements of farce, was here being presented as dead straight. Apparently, the Slav culture has little time for concepts like mock and satire. Amazingly, the drama worked just as well this way – it was certainly very moving, and at the premiere was given a standing ovation.

In Sofia I was invited to an event at the Swedish Embassy commemorating the 150th anniversary of August Strindberg’s birth. There I met a Swedish director who told me about a young up-and-coming Norwegian playwright called Jon Fosse. “He’s bound to be huge,” she told me. “Take a look at his work and consider translating him into English.

Jon Fosse.

Her predictions were correct. Today, fifteen years later, Fosse has had close to a thousand productions all over the world. He is on the Daily Telegraph list of 100 Living Geniuses and a hot candidate for the Nobel Prize in literature. A definitive analysis of his work is given in a fascinating book called The Luminous Darkness, written by international drama critic Leif Zern, translated into English by myself and published by Oberon Books.

In Fosse’s plays, Zern writes, man is shown to exist, not in the present, but suspended between the past and the future, between all that has been and all that might come about. His characters are caught in the eternal dilemma between their social persona and their inner life, between darkness and light, between appearance and reality. His style is minimalist, his dialogue neither vernacular nor literary, but offering a third dimension, in which we discern ourselves. Without ever resorting to the crude, violent or grotesque effects favoured by many contemporary playwrights, he manages to give dramatic form to the existential quality of life.

I started by translating his first staged play And We Shall Never Part, about an abandoned woman, and was immediately struck by the poetic quality of his language. Fosse writes in New Norwegian, a man-made language based on dialect, very expressive and favoured by poets. It reminded me of Irish, and I had a sudden vision of presenting this play in two language versions, back to back. The EU came in to fund the project and an excellent Irish translation was made by Máire Holmes. Fosse himself was very keen on the idea – he had spent some time living in the Gaeltacht, in Spiddal, and felt a great affinity with Ireland.

Though based on the same original script, the two versions showed up amazing differences, each reflecting the essence of Ireland’s two cultural traditions, emphasizing just how much language contributes to a nation’s identity. It makes a strong case for the promotion and fostering of the Irish language. However, the view in Ireland was that the scant resources available for Irish-language plays should be applied to the benefit of Irish playwrights, not Norwegians. Fifteen years later, we are still hoping to find an Irish theatre willing to share our enthusiasm for this project.

My translations of another two Fosse plays, Winter and Visits, published by Oberon Books, have had numerous productions in England and the U.S. However, as Fosse’s reputation grew, major theatres chose a different method of presenting his work in English: by ordering a basic, literal translation and then letting a named English-language playwright turn it into what he or she considered to be good dialogue.

The pitfalls of this method are easy to see: as the secondary playwright has no knowledge of what is truly being expressed in the original, the unique flavour of the author’s style cannot possibly be reproduced. Having translated over thirty plays, I know that it is not a word-by-word exercise, but more a matter of finding your way through the subtext: recreating the thoughts driving the drama, the patterns of speech defining each character and the actual rhythm of the piece as a whole. For that to be accomplished, you need to be thoroughly acquainted, not only with the two languages involved, but also with the intricacies of each culture.

This applies more than ever to the work of Fosse. Each play is like a house of cards: one false move – and the delicate balance collapses. I believe the reason why the English-speaking world has been so slow to embrace his writing is the attempts to present his plays in a processed, anglicized form.

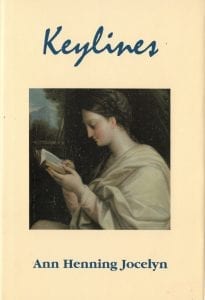

“Keylines”.

My work with Fosse extended over much of the Noughties. At the same time I became active as a broadcaster, mainly for the RTE programme A Living Word. The brief I was given was the best challenge any author could get: to express in less than 250 words an original thought, relevant to a major part of the Irish population listening in to Morning Ireland, of all different ages and interests, varying background and conditioning.

My contributions, transmitted regularly over ten years, received much attention from listeners, and a compilation called Keylines was published early on. It was intended for faithful RTE listeners, but the book soon took on a life of its own. To date it’s been published in seven European countries as well as in the U.S, India and China.

As I wrote my Keylines, I tended to arrange the text graphically in a pattern to reflect my train of thought as well as the rhythm of my breathing. I discovered that this made them much easier to present effectively. And when I returned to writing for the stage, I found the technique equally suitable to writing dialogue. Actors tell me the unusual lay-out lends itself to good enunciation and helps bring their character to life. Also, they find long speeches in this form easier to memorize.

I’m sure my close involvement with Fosse’s work influenced me in more ways than one. It brought me right back to my beginnings, to ancient Greek drama, to the tradition of Strindberg and Ibsen and, above all, to the theatre of Charles Marowitz: a theatre holding up a mirror, replete with meaning and applicable to all; created, paradoxically, to remind us of our own inner reality, as opposed to the roles we’re induced to play in the theatre of everyday life.

This kind of theatre goes beyond impressing audiences with brilliant performances or entertaining them by playing to the gallery. Whenever I hear critics and audiences eulogizing over good acting in a performance, I feel something’s amiss. It’s like seeing people arrive at their destination after a journey through a spectacular landscape and hearing them express their admiration for the skill of their driver. A theatrical experience should be embarked on assuming you’re in good hands – and leave you with an abiding impression that has little to do with its mechanics.

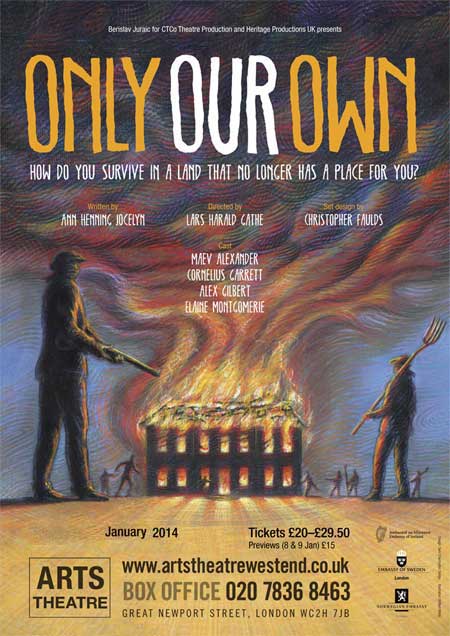

“Only Our Own”.

When I wrote my play Only Our Own, about a Protestant Anglo-Irish family searching for a place for themselves in an evolving Ireland, my main interest was to portray the emotional and social dynamics that, overtly or covertly, affect all aspects of life but come to the fore within home and family. I see the bringing of such awareness as an essential role for theatre – more so than ever in our time, as the use of advanced technology is making human communication increasingly distant and depersonalised.

Though it was thanks to modern technology that around this time, I was able to renew my working relationship with Charles Marowitz. Thanks to the net I tracked him down in Malibu, California. I contacted him to express my gratitude, to let him know how much his support had meant to me, but before we knew it, we were back working together, as if the intervening forty years had been a mere hiatus. Communication was via Skype and email Charles took an immediate interest in my first draft of Only Our Own and had some subtle but important suggestions for its further development. When the play was finished, he offered to come to Ireland to direct it, if I could interest a theatre or producer.

The Irish theatres I contacted had absolutely no interest in Marowitz’ progressive work. Perhaps they were reluctant to import an American director at the expense of his Irish counterparts. I can sympathize with that, but it does overlook the benefit Irish theatre professionals could have derived from the stimulus offered by someone of Marowitz ‘ stature.

Resistance to outside influence was something I had encountered before, trying for years to place Fosse’s work in Ireland. From my time as a shareholder at the Abbey Theatre in the late 1990s, I remember a clear policy to resist change, almost a duty to preserve and protect what might be called their own “brand”. I hope this attitude is a thing of the past. In his excellent book “Theatre and Globalisation”, Professor Patrick Lonergan warns about the danger of turning theatre into a brand. Branding, he says, stresses the concept at the expense of artistic merit, reaffirms prejudice and preconceived notions, and restricts national identity. Moreover, it undermines the main function of the theatre: to act as a genuine exponent of our status quo: there to broaden horizons, deepen understanding, and open new doors.

The only person prepared to open the door to Marowitz and myself was the late Mike Diskin of the Town Hall Theatre in Galway. Sadly his untimely terminal illness put a stop to those plans, and by now, Charles Marowitz, too, has left us.

After a successful production in London of my English version of Fosse’s play Visits, the director, a young Norwegian called Lars Gathe, contacted me, asking if I had any interesting work of my own. As a result, he mobilized the creative team of Visits for a London production of Only Our Own, and in January 2014, the play had its world premiere in The Arts Theatre in London’s West End.

Some of the English tabloid critics saw it as a serious deficiency that my Anglo-Irish aristocrats spoke without funny Irish accents and showed no sign of the Paddy-whackery they’d been led to expect from Irish plays. But better informed publications, like The Spectator and The Stage, gave it rave reviews. A provincial UK production and an Irish tour for Galway and Dublin of this play followed, but, with all the attention of the upcoming celebrations of the 1916 Easter Rising, was studiously ignored by Irish media.

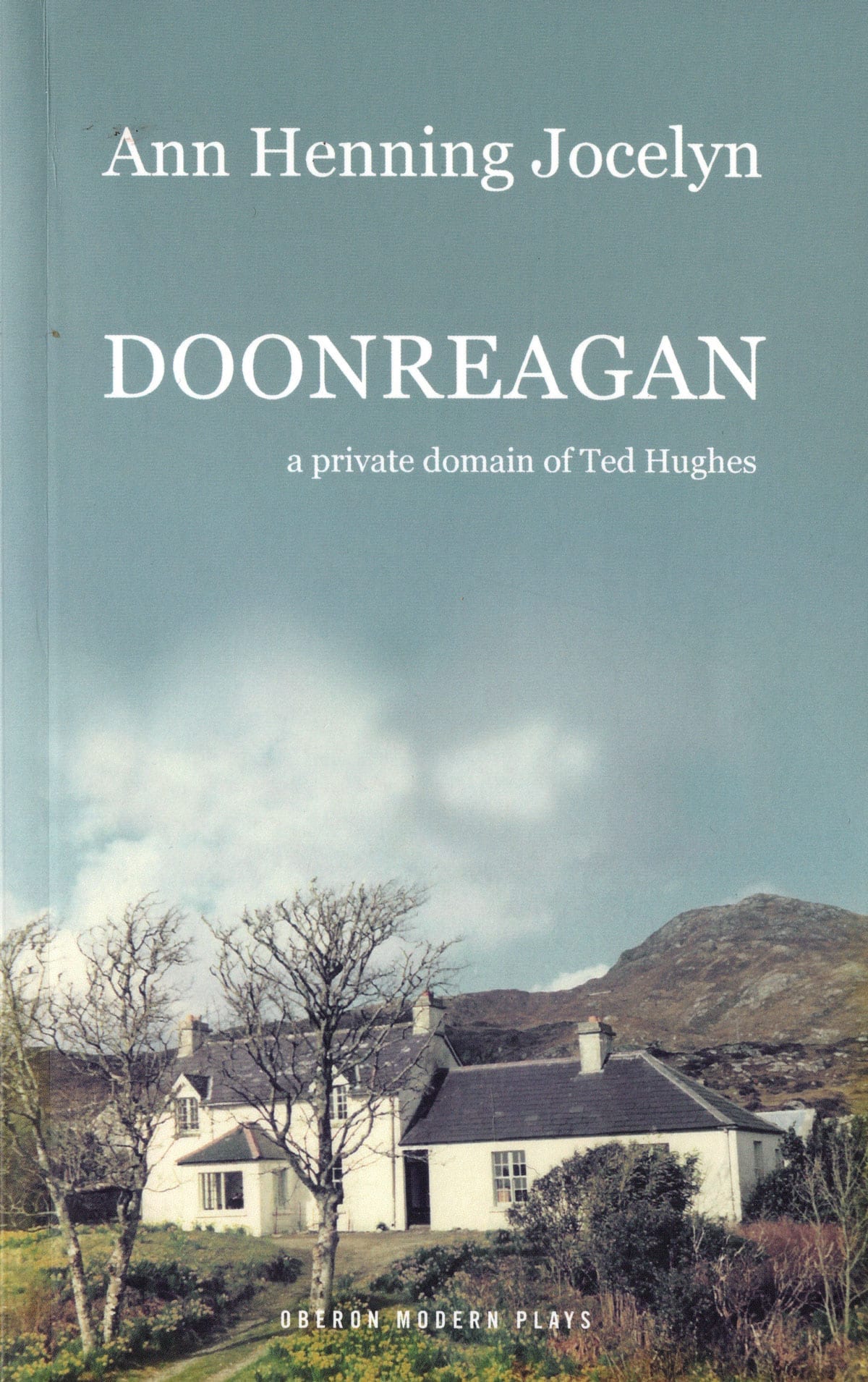

“Doonreagan”.

In the meantime, my husband and I had made a surprising discovery: that our home Doonreagan in Connemara had once been a favoured refuge for English Poet Laureate Ted Hughes. In his letters, published after his death in 1998, he refers to his time at Doonregan House as a breakthrough, in his writing and in everything to do with himself. Very few people knew about his escape to Ireland together with his partner Assia Wevill following the death of Sylvia Plath – it has been routinely overlooked by his biographers.

I was lucky enough to have access to the three friends who had been closest to him at the time: Seamus Heaney, Richard Murphy and Barrie Cooke. What they had to tell inspired me to write a play called Doonreagan. It was workshopped with Flora Montgomery and Daniel Simpson at the first Ted Hughes conference at Doonreagan in May 2013, and was very well received by the assembled authorities on Hughes. The play had its world premiere at Jermyn Street Theatre in London later the same year, with Daniel Simpson and Flora Montgomery as Ted and Assia.

Doonreagan explores the passionate but doomed relationship between Ted and Assia during their brief but intense spell in Connemara: their efforts to establish a common ground free from the towering shadow of Sylvia Plath; their longing for peace and contentment; and their discovery that, close to nature, away from the judgments, pressures, demands and expectations of the world at large, they came closer not only to each other, but also to themselves. My intention was to show how this kind of personal freedom brings you so close to your true self that the essence of your entire life – past, present and future – emerges as crystal clear and inevitable. The play reflects my growing interest, not so much in what happens to the characters in a play, but more why it happens, giving rise to the question why things happen at all – to you and me and everyone else.

In my view, theatre in today’s – not to mention tomorrow’s – world needs to aim further than presenting technically proficient drama. To continue to excel in the face of all new competition, modern theatre has to take full advantage of its unique power to affect: to cause a shift in spectators’ perception, challenge their outlook on life, enrich them with insights no other medium can offer.

My latest play, called The Sphere of Light, is an historical play, set in the 1500s. Like other plays of mine, it concerns itself, not so much with what actually happened, but more with the underlying forces that brought about events to change the course of world history. The “sphere of light” I see as a symbol of theatre itself – a space where a sharp light is shone on human affairs, so as to make them more intelligible. With the tendency of human nature to evade, suppress and deny, we need all the help we can get to access the ultimate truth. The truth about ourselves – which, at the end of the day, is all that matters.

Where Ireland is concerned, I perceive a need for change. With global audiences in a process of intense development, it won’t be enough to rest on the laurels of a triumphant past. To retain its place at the forefront of the world stage, Irish theatre will need to open up, to expand, out and forward. How to do this, within the framework of its excellent inherent theatre tradition, I see as a major challenge ahead.